location mapping and engineering housing

how houses are shaped by their environments

Rural communities are disproportionately affected by climate change in their region- some by droughts, others by floods and cyclones, and often by many at the same time. In fact, droughts and floods account for 80 percent of lost lives and 70 percent of economic losses in Sub-Sahara Africa. A huge part of this cost is infrastructure; there is an implicit assumption that land use planning, building codes, and standards provide enough requirements for building robust infrastructure. Today this isn’t the case because of variabilities with the climate, resources available, purchasing power, and a growing yet unstable need for housing often influenced by external factors. Building climate-resilient infrastructure would lead to a reduction in time and costs spent on repairs and overall maintenance.

an approach

Devising an approach to solving this problem requires narrowing locations and deciding where a solution would have the most impact as well as be the “easiest” to implement. To filter locations, we decided an optimal location criteria to answer the following questions:

(1) where is the government incentivized to solve this problem

(2) where are there multiple natural disasters occurring

(3) where is there limited housing insurance/housing insurance that is unaffordable

(4) where is the average cost of housing at least 20-30% of annual income

(5) where is there potential for on-the-ground feedback and validation

Understanding why these limits geographically speaking existed was a combination of our understanding of the problem and what it may take to execute quickly. In order for a solution to be viable, there must be stakeholders with a strong interest in investing in it. For housing to be affordable in developing countries, in particular, governments have commitments to get their residents housing. Housing insurance is a key factor in deciding whether people would invest in new housing infrastructure if their current insurance already protects them from damage. In the developed world, the majority of homeowners have insurance. In developing countries that are prone to climate disasters, insurance is usually not available as selling insurance in these scenarios is neither profitable nor possible because of the low purchasing power of the individuals they need to sell to.

Perhaps the most important consideration for a pilot is the idea that a potential solution would not involve rebuilding a house, but instead making an existing solution better. Realizing that floods and wildfires would require extensive rebuilding that is possible to tackle later, was the biggest learning to shifting our focus to low-hanging, neglected fruit that could still make marginal impacts on the world.

droughts

Drought events account for only 8 percent of natural disasters globally but pose the greatest natural hazard in Africa, accounting for 25 percent of all-natural disasters on the continent occurring between 1960 and 2006.

The root of climate-resilient housing with droughts is 3 main parts of the house: the foundation, the roof, and the wall.

When you go long periods of time without rain, the water within in clay and other soil-like material begins to evaporate, causing it to shrink. This forms cavity or gaps between the ground and your foundation. The foundation can crack as gravity pushes the weight of the house down into the gaps.

Another issue is the strong winds in dry periods associated with droughts that can weaken and damage the rooftops of buildings and houses. In reality, the type of roof and wall dictates the strength of the house to withstand these winds. Specific to roofs, the root causes of damage to them are larger wind velocity, small roof weight, insufficient anchoring of the roof to the building, and poor fixing of the skin to the roof structure. Having good skin involves exterior wall materials and designs that are climate-appropriate, robust, and perhaps aesthetically pleasing.

location

Where droughts are most prevalent - and perhaps where there is the most willingness to pay for climate-resilient housing is in Kenya where the government takes a special interest in developing good housing. Droughts are a difficult problem to solve because they have been variable and unpredictable, especially in the last 5 years.

Kenya’s situation is unique because it doesn’t face the same skill mismatch that many other countries in Africa do. Contractors, a key part of the housing design chain are expensive and not accessible to the majority of the population.

Kenya is a good case study for analyzing how willingness to pay, while important, is sometimes trumped by things like access to resources.

status quo

Kenya has different counties that have unique ways of living and traditions as well as various local needs and availability of construction materials, which influence a house’s vernacular architecture.

One type of house is a simple wattle and daub house, where a lattice of wooden sticks (wattle) is covered (daubed) with mud/clay/soil + a thatched roof. This is a very common type of housing in rural Africa but has been increasingly replaced by burnt bricks and concrete with metal sheet roofs.

Here’s a cool blog on building a simple wattle and daub house from scratch: https://www.themudhome.com/wattle-and-daub.html

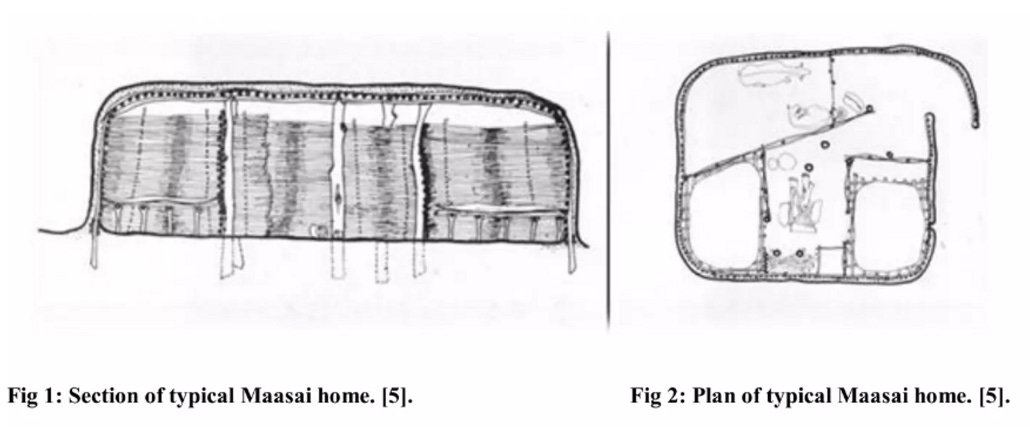

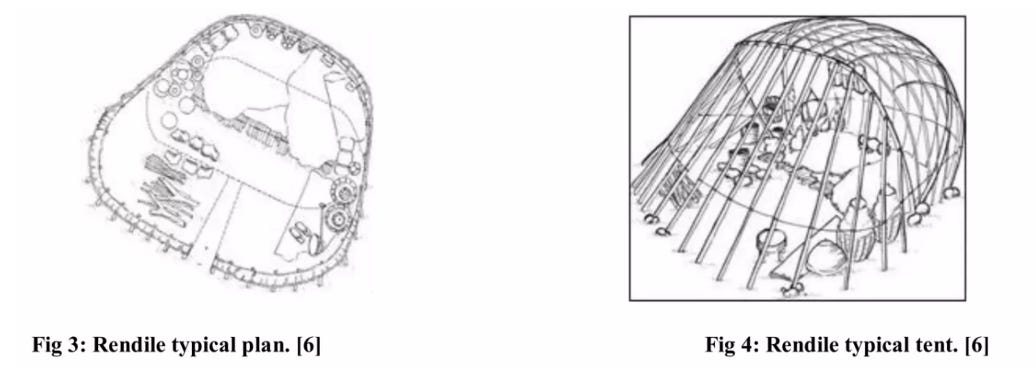

The Maasai are temporary houses belonging to a community of nomads (move from place to place a lot), so they need to be able to deconstruct and construct easily. Their simple frame structure is made from twigs, soil, grass, and cow dung. The wall is soil, cow dung, and ashes mixed together, with a dry grass roof that is overlaid. It is generally 3m x 5m x 1.5m tall.

The Taita are circular houses that have no wall partition within them. Poles made of sticks are connected to the center pole with a thatched roof made of grass. The roof is laid in layers to enhance protection from direct sunlight. The walls are made up of mud and brackets.

The Rendile are Pre-arched frames of sticks from trees of nearby rivers (locally sources) are tied with ropes of long leaves. If the ground is soft, the frame is buried about half a meter; otherwise, stones are put around the base to stabilize it. It is about 3m wide and 2m high and is resistant to being blown away by strong winds, even though it does usually sway.

common materials used in Kenya’s houses

Roofs:

82% = Iron Sheets

14% = Grass/Thatch/Makuti

makuti are palm tree leaves that are cooler but require higher maintenance + can catch fire and spread easilty

2% = Dung/Mud

2% = Other

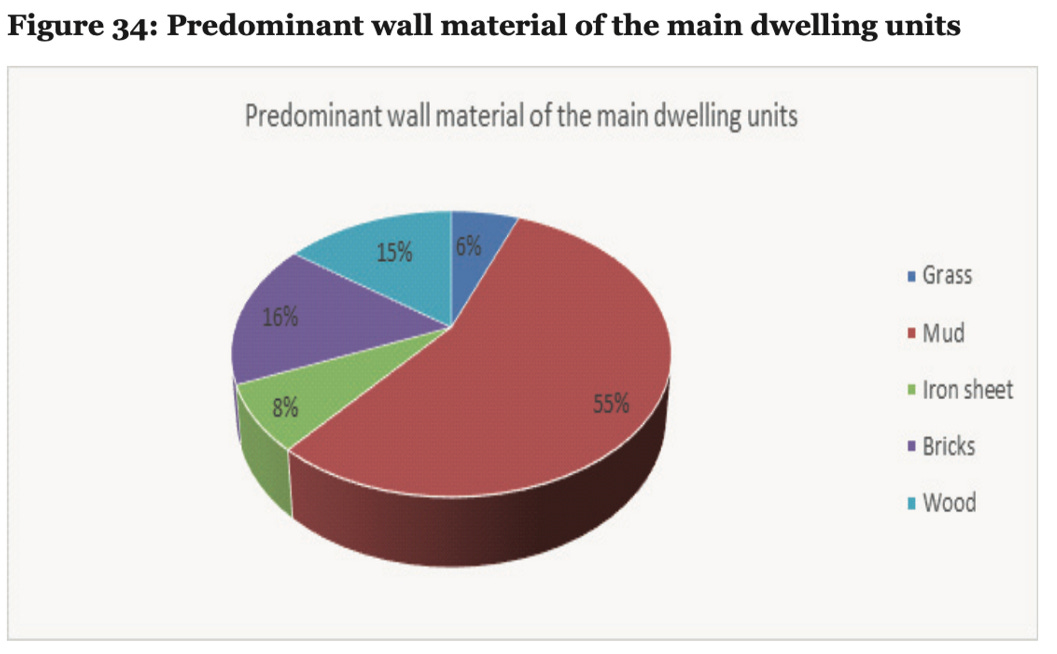

Wall:

55% = Mud

16% = Bricks

15% = Wood (not as common since it detoriates easily)

8% = Iron Sheet

6% = Grass

Foundation:

muram (mix of soil and sand)

cement (mix of water and sand - binds bricks)

ballast (gravel - supports weight)

stone (create foundation)

soil + sand (level foundation)

the heavier the house, the stronger the foundation needs to be → foundation is based on that

problems

thermal mass

Due to the of the scorching temperatures in regions like Kenya, a high thermal mass provides comfort to residents. When the temperature is hot, the thermal mass of the material determines how long it takes for the heat that is absorbed in the material to get into the house. Ideally, when the heat is absorbed by walls and floors during the day, it radiates into the house during the nighttime when it tends to be colder. By the next morning, the home is cooler and the temperature is stabilized.

For instance, glass has a short thermal mass, but the grass has a high thermal mass.

A paper based on surveys done in Kenya has shown that residents think “it is very uncomfortable to stay in [their] houses that are made of metal sheet” and “Houses are made of metal sheet that doesn’t keep the heat”. The status quo, where 82% of roofs and 8% of walls are made from iron sheets, isn’t convenient for many people because iron gets hot fast, leading to a low thermal mass (despite being robust so less maintenance is required).

With drought-like weather, a potential alternative should have a higher thermal mass like grass but also be as robust + require less maintenance like iron sheets

community/culture

Despite iron sheets being pretty common, they’re still expensive so one would reasonably assume that some places just can’t afford it. However, one thing to consider is the culture. Instead of getting something installed by a masonry worker (which we will explain more in a bit), many like to partake in community-intensive things where people build together. This is a small percentage of people because most use masonry workers/a contractor if accessible, but something to still consider

stakeholders

The Kenya government has made a commitment to build 250,000 houses every year

They employ contractors to see the construction of these homes. When big building projects aren’t available, the government doesn’t employ contractors. Contractors are engineers and architects so they tend to be expensive.

When building a home, people look for masonry who don’t have as much solid experience planning and understanding homes which lead to fragility and ineffective housing because of a lack of planning.

Key insight: there is a lack of materials in Kenya, but if the materials were deployed more effectively there likely wouldn’t be any. My hypothesis is that if contractors were responsible for every home, materials would be used better.

The reason why contractors aren’t employed by the general public is that they need money to work and governments who have more at stake for the failure or success of housing or any major building have the incentives to fund contractors.

Masonry tends to be free people in Kenya who work like freelancers- they know how to build things and are usually employed by people who are building houses.

People are incentivized to find comfort in their homes, especially with high temperatures. Some of the materials/structures of houses that would incentivize them are having:

good thermal mass to keep them cool during the day and warm during nighttime

something robust that can resist a drought’s strong winds but also that doesn’t deteriorate easily

airflow - having some sort of cross-ventilation allows the cooling of homes in drought-like conditions. it is recommended that there is a balance of fresh air coming in and going out

affordability - if a household can acquire a housing unit for an amount of up to 30% of its household income, then housing is considered affordable

Looking into the landscape of current solutions now and talking to experts, what we aim to prioritize is the focus on simple economically incentivized innovation bringing asymmetric returns on improving climate housing.